Polyvagal Theory, Herbalism, Resiliency and Healing

Today we are experiencing epidemic levels of anxiety, depression and other forms of mental illness. Researchers have honed in on the usual culprits of stress, poverty, past trauma and oppression. But one scientist named Stephen Porges focused in on how humans process and adapt to severe stress and devised a new concept known as polyvagal theory. This theory shows how humans can engage and help each other to build nervous system resiliency, overcome stressors, and help us heal from trauma and emotional suffering.

The Nervous System

Lets start at the beginning. If you remember back to high school biology class, the nervous system is comprised of the central and peripheral nervous system. The peripheral nervous system is divided up into somatic (voluntary muscle movements) and the autonomic (automatic regulation of systems like the heart and respiration.) And the autonomic is divided up into the sympathetic and parasympathetic- the yin and yang of the nervous system.

The sympathetic gets us ready for action via fight or flight, helping us to face predators and other threats. The parasympathetic helps us to stay calm and relaxed and to help us “rest and digest”. Both the gas and the brake are needed for managing our environment but there is a further evolutionary adaptation that has happened just for mammals- a third way that moves much quicker, and allows us to override the more primitive nervous system responses. This is known as the Social Engagement System and is at the root of how human’s attach to their parents, manage stress and can eventually heal from the damaging effects of trauma.

Dr. Stephen Porges is director of the Brain-Body Center at the University of Illinois in Chicago. In 1994, he developed this three part nervous system idea that he called Polyvagal theory. To understand it, lets take a quick look at the vagus nerve.

The vagus is the longest nerve in the body, running from the brainstem down through the back of the throat and extends through the chest and abdomen, extending its nerve fibers to the heart, the lungs and most of the digestive tract. It consists of a more primitive unmyelinated portion known as the dorsal vagus as well as a more evolutionarily advanced myelinated portion only found in mammals known as the ventral vagus.

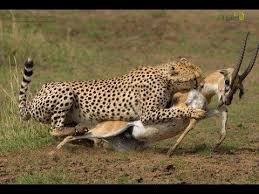

The primitive dorsal vagus acts as a shut down mechanism, causing us to freeze or faint when it is activated. You can picture this by remembering those nature videos that show a gazelle fleeing across a plan while a cheetah chases it. At the last second before being attacked, the gazelle stops and lays on the ground in a frozen state. The dorsal vagus has been activated in response to an overwhelming threat. There are two possibilties here- one is that this is a last ditch attempt to throw off a predator by “playing dead”. Or more likely it is a creature’s preparation for overwhelming physical and emotional pain.

Similarly, humans will freeze due to perceived overwhelming threats. At first stress and perceived threats may lead to a sympathetic nervous system response, a hormonal cascade leading to a fight or flight response. But severe trauma like an abusive father or an overwhelming experience like a car accident or violence can cause the dorsal vagus to be activated and a person to freeze and dissociate. This is a nervous system protective mechanism against a severe threat. An individual literally does not have the bandwidth and capacity to manage the horror of the situation and dissociates and freezes. While this is protective, it can become imbedded as a neurological pathway and even minor triggers can cause the individual to dissociate as they grow older.

Polyvagal Theory

Now lets examine that third way Porges talked about. The more evolutionarily modern mammalian ventral vagus nerve is connected to important receptors in the eyes, ears and face. Humans pick up on subtle social cues such as eye contact, smiling and vocal intonation to determine safety in a social environment. Porges calls this constant monitoring of our environment for cues about safety “neuroception.” Receptors in the face pick up these social cues and send signals to the ventral vagus which can then act to calm the heart and nervous system.

Imagine a young child of 18 months old crying out for a parent to come. Perhaps they have just fallen down and scraped their knee. In a healthy environment, a parent will come and soothe the child via eye contact, smiling, and making gentle cooing noises. Those receptors on the face and the ears have received signals that are then transferred to the ventral vagus. The vagus then sends chemical messengers in the form of acetylcholine to the heart to slow the pace and relax the arteries. This is the social engagement system at work. Instead of going into full fight or flight, or into a freeze state, a parent activates the ventral vagus to override the more primitive nervous system response and help a child feel calm and safe.

Now imagine the other possibility. The child cries out but the parent doesn’t come soon, or worse- yells at the kid and does not soothe them. If this happens repeatedly, then the child never learns how to override the primitive response of fight, flight or freeze and becomes stuck in easily returning to those states again and again, even with small triggers.

This is the essence of what happens in developmental trauma. Poor attachment and ongoing abusive environments keep a child locked into an endless cycle of reacting to stressors via fight, flight or freeze. They are unable to easily self-soothe because their nervous system has been trained by neglect or abuse to stay in a heightened stress state.

So Porges is pointing us to this third option known as the Social Engagement System- the idea that human to human face to heart contact could help us avoid the more primitive circuitry to override severe nervous system responses to stress. Here is another example. Imagine you are in a movie theater and suddenly you see a man at the door of the theater acting erratically, yelling and cussing. At first you may start to get extremely anxious and keyed up- the fight or flight sympathetic state, but you look around at your friends and others. Through reading eye contact, facial expressions and hearing a few words, you come to realize that the man is not a threat but just drunk and is being escorted away. Social engagement signals your ventral vagus to send calming signals to the heart to override fight or flight.

Social engagement systems are key to developing a healthy response to stress. They are also key to helping people heal from trauma. A child who did not receive adequate care and love will be challenged to self-soothe and may feel the world is an unsafe place. Trauma as a child can lead to coping strategies that are damaging such as drug and alcohol abuse, addiction, self-injury and suicidal behaviors. Those that are labelled “borderline” often have experienced childhood trauma. To overcome these imbedded neurological pathways, its key to develop ways of strengthening what is called “vagal tone”- the ability to stay in a restful parasympathetic state even in the face of adversity.

There are numerous ways that we can strengthen vagal tone, relax the nervous system and utilize techniques to soothe ourselves and build resiliency. Here are the 5 that I recommend most frequently.

Breath work. Focusing on a longer exhalation is key here and I like to use a simple technique of breathing in for four seconds, holding for a second and then breathing out for 8 counts.

Yoga, Qi Gong and Dance- All these are ways that improve flow and help move us out of rigid and frozen states to allow the body to flex, extend, open and release.

Singing and chanting- the vagal nerve runs from the brainstem down through the back of the throat to the organs. We can stimulate parasympathetic relaxation via stimulating the vagus through singing and chanting. Thats why you feel so great after belting out Bohemian Rhapsody at the karaoke party.

Laughter- Along with singing and chanting this is the other low hanging fruit of vagal stimulation. Los of people aren’t going to start a yoga practice, but many will watch comedies and dumb movies that make them laugh. That laughter also stimulates the vagus to encourage relaxation.

Body work- Massage and acupuncture are both forms of body work that help stimulate the vagus and encourage rest and healthy digestion.

But at the core, there is only so much that we can do to self-regulate. Humans are social creatures and healthy relationships are key to our sense of safety, well being and emotional wellbeing. If our relationships are poor, and we are hanging out with people we don’t trust, who are emotionally distant or even abusive, it will be next to impossible to heal from the scars and wounds of trauma. To fully heal, we need healthy, trusting relationships and social engagement systems as a way of strengthening this calming ventral vagal pathway. Loving face to face and heart to heart connections are at the core of how we can heal from patterns of fight, flight or freeze.

Plants, Social Bonding and Emotional Self-Regulation

I want to shift to exploring how the plant world, as well as social engagement and bonding, are key pieces of helping people build resiliency and heal from emotional distress. Lets start with the tree Western Red Cedar. Its a beautiful copper barked evergreen with long sweeping branches and fine articulated aromatic leaves that grows commonly in the Northwest. From building homes to making clothing, utensils, medicines, smudge, baskets and canoes, cedar has long played a central role in the lives of native Northwest peoples. Native peoples spent an enormous amount of time cutting, stripping and carving cedar into practical everyday tools, clothes, homes and transportation. Imagine small groups of people engaging in this work day in and day out. Social bonding developed as they worked with this tall tree. It became central to their sense of place and social cohesion.

As settlers turned people away from working in multiple ways with cedar towards modern activities such as trapping, logging and then factory and city work, that deep connection and interweaving was damaged, wounded. This one tree was the template for building practical living skills, social engagement and bonding as well as for cultural identity and resiliency.

Today, indigenous tribes from throughout the Northwest gather to engage in “Canoe Journeys”. These are gatherings where tribes bring many dozens of canoes built of cedar to paddle and navigate the Northwest waterways. After hundreds of years of colonization, wars, plagues, displacement and forced assimilation, the canoe journeys are a way back, to reconnect to cultural legacies and to each other in shared pride in heritage and a way to strengthen living traditions. The Cedar tree plays a central role here in bringing these indigenous groups together via carved cedar canoes. Greater social resiliency is key to improved mental and physical health. Healing is a group endeavor.

What we are talking about is that plants build resiliency through social engagement and bonding. The most common way that we develop social bonds is around the patterns of meal preparation and gatherings. Traditionally, cultures throughout the world centered meal preapartions around the seasons and when particular foraged roots, berries and crops became available. Think of Biblical traditions around the breaking of wheat bread, the consumption of cacao in meso-american societies or the importance of corn and beans to central and north American Indigenous groups. These plants have acted as key agents that help bind us to each other in the shared experience of drinking and eating meals together.

Cacao Beans

Another way plants help build social bonding is through their power to stimulate, sedate and innebriate. The process of fermenting fruit and grains has brought us cider, wine, beer and mead. Add to that tea, coffee and cannabis and arguably you have the most important plant based social bonding agents on the Earth. And yes they all give a buzz, but they do something greater than that. They are consumed in taverns and bars, tea and coffee houses where people engage with each other- do business, sing karaoke, laugh, play and bond.

In the polynesian islands, the root of the kava plant is consumed regularly for its sedative and euphoric buzz, in rituals and casual social settings. Kava is key to relaxing the nervous system to improve openness, and receptivity during social engagement.

Plants can act as mediators to strengthen social bonding in other ways as well. From group hikes in nature to gardening to the Japanese relaxation practice of Forest Bathing, the natural world helps strengthen parasympathetic vagal tone to help us to feel more calm, receptive and socially engaged.

Ways that plants act as mediators for social engagement to strengthen vagal tone:

Shared Meals. Simply the act of eating together and sharing meals in a harmonious way with positive, trusted friends and allies helps build social engagement pathways that improve vagal tone. This is especially the case if there are particularly cultural foods that are important and act as a hub at feasts, holidays and gatherings.

Stimulants, relaxants and Inebriants. Yes I know this might be controversial as there can be many side effects and addictive potentials to these plants. But coffee, tea, kava, cacao, beer, wine and ciders made with plants and fruits have long been agents to strengthen social bonding and improve a sense of social safety that can translate into greater vagal tone.

Cultural Keystone plants. These are plants that are essential to the wellbeing and health of particular societies. They are not easily replaceable and they are used in a variety of important functions. Western Red Cedar was one example. Others include the native use of tobacco, sweetgrass, cacao, copal and sage. In the old world, grapes, olive trees, frankincense, myrrh and many other plants have played a key role in social bonding, cohesion and resiliency.

Herbs that improve vagal tone. A number of herbs help improve vagal tone in a variety of ways. From bitter tonics that stimulate the vagus directly, to “nervines” that help to relax the nervous system via neurotransmitter receptors. Think kava, valerian, passionflower and chamomile. A great article on the subject comes via Nikki Darrell called Re-establishing Good Vagal Tone and Balance with Herbs.

Gut health. Along with shared meals with trusted, loving people, there are certain herbs that improve gut health that in turn lead to greater vagal tone. Some herbs act as “prebiotics”, feeding healthy bacteria in the gut microbiome. Some include herbs such as burdock and dandelion roots. These healthy bacteria then act to stimulate the vagus to improve parasympathetic relaxation. For more in depth information about this, please see my article Trauma, the Gut and Healing: Building Deep Resiliency

Conclusion

The importance of plants as mediators of social bonding is key to our understanding of how to help people heal who are stuck in maladaptive patterns due to trauma, anxiety and depression. We often think of ourselves as individuals with discrete physical and emotional diseases but in reality we are part of a much larger social and environmental fabric. Poverty, oppression, trauma and social stressors are often the primary cause of illness patterns. Sadness often stems in part from a sense of disconnection and alienation from our families, friends, the land, the seasons and our own good hearts. Polyvaggal theory teaches us that we can overcome this sense of disconnection that leads to poor emotional self-regulation by paying attention to the importance of human to human, heart to heart engagement and bonding. Plants can act as those mediators that bring us back into greater connection and emotional wellbeing.

Links:

The polyvagal theory: New insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system Stephen Porges

Cultural and Religious Keystone Species- The Need to Desacralize Nature Al Zein and Musselman

Cultural Keystone Species: Implications for Ecological Conservation and Restoration Garibaldi and Turner

Esther Cherland

The polyvagal theory: phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system. Stephen Porges

Re-establishing Good Vagal Tone and Balance with Herbs Nikki Darrell

CPTSD, Allostatic Load and Giving no Fucks by Gwynnie Hale

When The Trauma Doesn’t End Romeo Vitelli

How I’m Recovering from C-PTSD Liz Lazzara

Polyvagal theory in practice Dee Wagner

The Body Keeps The Score Bessel Van der Kolk

This article written by Jon Keyes, Licensed Professional Counselor and herbalist. For more articles like this, please go to www.Hearthsidehealing.com.

You can also find me at the Facebook group Herbs for Mental Health.